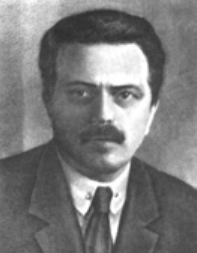

Andrzej Tretiak (1886-1944)

A Tale of (Dis)continuity

There is hardly an academic tradition which can more readily acknowledge the importance of founding myths than the philological one. The stories of origin are the raw material of classical inquires but they also alert us to the authority of a well-cultivated inheritance. The sense of continuity receives the necessary tribute with jubilees and anniversaries but it also – perhaps even more importantly – activates when legacies dissolve or crises unfold. Thus, our founding myths, with their records of obstacles, losses, and failures, the unnerving narratives about victories won at a heavy price, or fatal turns remedied by sacrifice or unusual persistence, motivate and console without, however, lulling us into a false sense of security. To us, (neo)philologists, these hopes often translate into neat formulas such as “the pen is mightier than the sword”. And yet even as we preserve and celebrate the memory of texts, we cannot but grieve over the untimely loss of their authors. The life and works of Andrzej Tretiak (1886–1944), the first Professor of English Literature at the University of Warsaw, has already been subject to scrutiny on several occasions, beginning with the heartbreaking inventories of academics who perished during the Second World War, through commemorative essays to, finally, fullyfledged critical studies of the interwar period. With time, however, the life of this pioneer of English Studies in Warsaw has gained renewed relevance, as we proceed from a meticulous reconstruction of facts to a more general reflection on the fortunes of intellectuals at the turning points of history. In particular, there were two defining moments which shaped Tretiak’s academic career: first in 1922, when he accepted the task to set up the first English Seminar at the University of Warsaw, and then again, in 1939, when he became Dean of the Faculty of Humanities. His first decision was connected with the reformist movement which foregrounded the dynamics of vernacular cultures, rich and thriving, clearly breaking free from the time-honoured hegemony of classical philology. This somewhat transgressive gesture matched the mood of the first decade after regaining national independence by Poland in 1918, a most challenging period, when universities reorganised to implement national policies and catch up with European academic practice. The second decision came at an extremely trying time and entailed responsibility for an academic community far larger than Tretiak’s immediate scholarly circle.

Accepting deanship in 1939 left Tretiak little time to consolidate the Faculty. In the occupied city, Tretiak turned to clandestine teaching and administrative work, and adopted a cover name, a wise precaution which in 1944 helped him survive imprisonment in the notorious Pawiak jail. The joy of release at the end of July 1944 was brief. Tretiak was shot dead on 3 August with a group of other university professors, all dragged out of their house at Nowy Zjazd 5 and hurled to a brutal execution in the next street. Soon afterwards, Tretiak’s son, Tomasz, also perished at the hands of Nazi soldiers. The demise of the Tretiak family could not but hasten the demise of the field of study, a decline deepened by the loss of Professor Władysław Tarnawski (1985–1951), an eminent Shakespeare scholar based at the University of Lwów and the Jagiellonian University who was tortured to death in the Rakowiecka prison.

The final tragic trajectory of Tretiak’s academic career bears witness to the annihilating power of war and the fragility of academic structures where the exclusive human factor takes precedence over material substance or sheer numbers. And yet it is the totality of Tretiak’s academic experience, as much as it can be construed and interpreted, that makes this figure particularly appealing and, in a way, authentic. Hence the sense of striving and achievement go hand in hand with the feeling of exhaustion and disillusionment to the effect of taking up a completely novel course of studies, dropping his teaching post, and moving away from the city to manage country estates. This pattern of ebb and flow, the weird dichotomy of the life of a university founder and a university fugitive, show Tretiak as an intellectual in search of a refuge where he could pursue his engagement with literature free from the distresses of academic life. The contemplative urge remains in perfect harmony with the way of processing his experience during the war. Cold and trembling, Tretiak falls back on the familiar literary texts to search for clues for his own time.

In 2019, when the Institute was recalling the 75th anniversary of Tretiak’s death, one was inclined to think of it as an ancient martyrdom, encapsulated in a distant crisis, closed and overcome. Yet the year 2022 has taught us a different lesson and activated a different sense of continuity. After all, witnessing his world falling apart, Tretiak read and taught what we too endlessly read and teach, clinging to the well-rehearsed images of human misery and the hope beyond them. This is the case of William Butler Yeats’ Easter 1916 whose refrain and ending become for Tretiak, somewhat prophetically, the source of a private epiphany he sharein a letter from 1941:

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

How did he come to trust it?

Professor Andrzej Tretiak was born in Lvov into a family with academic traditions. His father, Professor Józef Tretiak, was affiliated to the Jagiellonian University, and specialised in Slavic literatures (Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian). Andrzej Tretiak became a graduate of the Jagiellonian University where he studied English, German, and Polish literature (1904–1907) and where at the age of 23 he earned his Ph.D. based on a dissertation entitled Über “hapax legomena” by Shakespeare, the first ever doctoral work written by a Pole on English literature and supervised by Professor Wilhelm Creizenach, a German scholar based in Kraków. In the years that followed, Tretiak strived to establish himself as a researcher of English Renaissance literature, an ambition evidenced by his monograph of 1910 on the epigrammatic output of John Harrington (1561–1612).

The apparently swift progress of Tretiak’s academic career was halted by what was described later as a nervous breakdown, though, perhaps, was a very wellgrounded decision to secure time for creative work. In 1910, he decided to study agriculture at the university in Wrocław (at that time a German city) and, upon graduation, undertook the management of country estates. Once married, in 1914, Tretiak became father to two sons (in 1914 and in 1920). The years away from academia proved naturally conducive to his literary endeavours, Shakespeare and Scott translations in particular. In 1919, Tretiak became the editor of the (now monumental) new series of the Ossolineum National Library, taking the responsibility for the critical editions of English literature. The year 1921 saw the publication of The Tempest and Macbeth, both edited by Andrzej Tretiak and translated by Józef Paszkowski, i.e. the canonical 19th-century translator whose work Tretiak freely amended. The two volumes were soon followed by Tretiak’s own translation of Hamlet (1922) and King Lear (1923), and yet another volume with Paszkowski’s translation of Othello (1927) edited by Tretiak.

When, in 1922, Tretiak accepted a post at the newly established English Seminar at the University of Warsaw, this prestigious task clearly impeded his work as a translator and editor. The subsequent years saw a flurry of critical essays by Tretiak, proving his increasing focus on the dramatic structure and imagery in Shakespeare’s plays but also venturing into other literary realms, English Romantic poetry in particular. In time, Tretiak specialised in erudite prefaces, introducing into Polish critical discourse the oeuvre of an impressive variety of English authors such as Oscar Wilde, Joseph Conrad, George Bernard Shaw, Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, John Galsworthy, or James Matthew Barrie. This major critical input served the needs of the increasing number of trained (neo)philologists, but left Tretiak with little time to pursue his own critical path. Nevertheless, he was the first Polish Shakespeare scholar whose article appeared in a major English periodical on literary history. Published in 1929, “The Merchant of Venice and the ‘Alien’ Question” was a bold interpretative proposal, backed by a meticulous analysis of the original social context as well as an acute understanding of more universal tensions likely to emerge in multiethnic urban communities. Tretiak linked the play with the wave of anti-alien riots in London, culminating with the Tower Hill Riot of 1595 and the public hanging of riotous apprentices. Shakespeare’s alleged preoccupation with the fate of continental emigrants,

French, Walloon, and Flemish refugees, further evidenced by the compassionate passages in Sir Thomas More which Tretiak, as much as the majority of contemporaneous scholarship, ascribed to Shakespeare, was a key to the understanding of The Merchant of Venice. At stake, he argued, was the legal status of aliens, the right of denizens to appeal to the same courts and invoke the same laws, and the play’s problematic resolution suggesting that the differences of blood and religion can be obliterated no sooner than in the second or third generation by intermarriages or conversion. In his reading of the play, Tretiak seemed at odds with the criticism of his time, but he also dramatically differed from post-Holocaust criticism which dominated the 20th century. His insights, however, prefigured many of the contemporary approaches to the play which focus on the status of minority groups in otherwise homogeneous societies.

Today, most of the works of Tretiak fall into the symbolic realm of national heritage rather than serve as academic reference. Neither his translations nor his prefaces have survived in critical discourse, a necessary fate of all rewritings replaced by new endeavours. As much as the relevance of our critical insights may fade away, they still have their local habitation and a name, none of which can be neglected. In the history of English Studies in Poland, Andrzej Tretiak appears to be a somewhat evangelical farmer who sowed a multitude of seeds of which many appear to have perished before given a chance to grow, including the sower

himself. Tretiak’s influence can hardly be measured by pure academic effectiveness. What transpires from his biography is a powerful testimony of a different kind: from him we would do well to learn to trust in literature as a record of human experience and aid in adherence to ethical values when they are most tested.

Anna Cetera-Włodarczyk

Wirtualna wystawa o Prof. Andrzeju Tertiaku

Sylwetka Prof. Andrzeja Tertiaka jako tłumacza dzieł Williama Shakespeare'a

References:

Borowy, Wacław. “Wspomnienia pośmiertne: Andrzej Tretiak (1886–1944)”, Rocznik Towarzystwa Naukowego Warszawskiego 1938–1945, no. 31–38, 262–264.

Helsztyński, Stanisław. “Andrzej Tretiak”, Pamiętnik Literacki, 1946, no. 36/3–4, 398–404.

Jabłkowska, Róża. “Prewar English Studies at Warsaw University: Luminaries and Graduates”, The Fiftieth Anniversary of the English Department, University of Warsaw, 1923–1973: Jubilee Volume Containing Materials Prepared for the Session Held on 2d June 1973, Zofia Dziedzic (ed.), Warsaw, 1975, 13–23.

Jaworska, Anna; Anna Cetera-Włodarczyk. Exhibition Commemorating the 75th Anniversary of the Death of Professor Andrzej Tretiak, Faculty of Modern Languages – Institute of English Studies, University of Warsaw, 2019, and online http://tretiak.wn.uw.edu.pl

Kowalik, Barbara. “Z kart warszawskiej neofilologii: dwieście lat i dobry początek”, Acta Philologica, 2016, no. 49, 7–28.

Stanisz, Elżbieta. Kierunki polskiej szekspirologicznej myśli krytycznej w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym. Toruń, Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, 2011.

Tretiak, Andrew. “The Merchant of Venice and the ‘Alien’ Question”, The Review of English Studies, Oct. 1929, vol. 5, no. 20, 402–409. URL: www.jstor.org/stable/508234